This post originally appeared in the monthly farm animal welfare newsletter written by Lewis Bollard, our program officer for farm animal welfare. Sign up here to receive an email each month with Lewis’ research and insights into farm animal advocacy. Note that the newsletter is not thoroughly vetted by other staff and does not necessarily represent consensus views of Open Philanthropy as a whole.

It’s hard to convey the scale of modern chicken production. One US poultry company, Pilgrim’s Pride, slaughters more animals every week than the entire US beef and dairy industries slaughter in a year. Globally, more farmed chickens are alive today than all other domesticated birds and mammals combined.

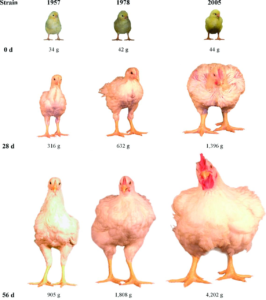

The most numerous of these chickens are the world’s roughly 15 billion “broilers” alive at any time — or roughly 55 billion slaughtered annually. (A “broiler” is technically a young chicken, but the term now covers almost all chickens raised for meat, since almost all are slaughtered before sexual maturity.) American broilers aren’t caged or fed hormones — though both practices are catching on elsewhere. But they are bred to suffer, and overcrowded on wet litter in dimly-lit sheds, before being inhumanely slaughtered.

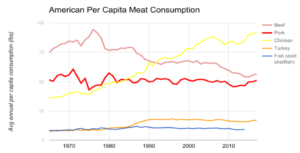

Broiler chickens have suffered for their efficiency and versatility. US broilers now gain a pound of weight for every 1.9 pounds of feed they eat, and reach a slaughter weight of 6.2 pounds in just 48 days. Unlike pork and beef, their meat is accepted by most major religions, and widely viewed as healthy and environmentally friendly. It’s no wonder that 94 percent of Americans consume chicken. And because chickens are so small, each of those Americans wolves down about 23 chickens every year — more than the number of cows the most carnivorous American will eat in a lifetime.

Now, in the Year of the Chicken, broilers’ fortunes may finally be looking up. At the end of last year, America’s two largest foodservice companies — Aramark and Compass Group — committed within hours of each other to enacting major broiler chicken welfare reforms by 2024. Their pledges followed campaigns by Mercy For Animals, Compassion in World Farming USA, The Humane League, and the Humane Society of the United States.

Since then, these and other groups have secured similar commitments from 27 major food companies, including fast food giants Burger King, Chipotle, and Panera. Five of these companies have committed to only buy chicken certified under the Global Animal Partnership’s (GAP) new broiler welfare standards, which will address everything from genetics to slaughter once finalized. But most companies have only pledged to adopt a more limited set of reforms.

So what are these companies actually committing to, and what impact do we think these reforms will have for broiler chickens?

Advocates have chosen to seek corporate pledges to address four of the chicken welfare problems most commonly cited by scientists. But it’s worth noting that much animal welfare science is either poorly designed or biased by industry or interest group funding. It’s also hard to know what chickens actually feel — we can only observe their preferences, behavior, stress, health, and other indicators.

Specifically, companies adopting the more limited reforms — and not GAP certification — have agreed to third party auditing of their poultry suppliers against the following standards:

- More space: To provide chickens with one square foot per six pounds of weight — about 40% more space than the industry standard. Studies show both that chickens seem to prefer more space than they receive, and that overcrowding worsens air and litter quality, exacerbating heat stress and dermatitis.

- Better environments: To provide chickens with clean litter, enrichments like hay bales, and six hours of continuous darkness each night coupled with proper lighting during the day. Most producers currently provide just four one hour increments of darkness each night, and 20 hours of dim lighting, because this encourages birds to eat more. And producers routinely use the same litter for six or more consecutive flocks, or even multiple years, resulting in later flocks living and sleeping atop large piles of manure.

- Better genetics: To use only breeds found to have higher welfare outcomes, based on the outcome of an upcoming study at the University of Guelph. Modern broilers are bred for rapid breast meat growth, and their respiratory systems and legs can’t keep up, leaving many lame and in such pain that they’ll self-select pain relief.

- Less inhumane slaughter: To move to multi-step controlled atmospheric stunning systems, in which chickens are stunned with gas or oxygen removal in their transport crates — eliminating the possibility of rough handling — and more reliably rendering birds unconscious. The current electrical waterbath stunning method requires workers to shackle multiple birds per second, resulting in broken wings and legs, and only lightly shocks birds, possibly paralyzing rather than stunning them. As a result, nearly one million US chickens are boiled alive each year.

Advocates are making great progress in these campaigns, but there’s still much more work to do. My estimate is that the corporate pledges to date should cover 300-700 million chickens per year once implemented. Now advocates need to ensure that implementation actually happens, while securing pledges from larger brands, like Subway and Wendy’s, with the potential to affect hundreds of millions more chickens.

Next month I’ll address the only farm animals more numerous and ignored than broiler chickens: fish.