This post originally appeared in the monthly farm animal welfare newsletter written by Lewis Bollard, our program officer for farm animal welfare. Sign up here to receive an email each month with Lewis’ research and insights into farm animal advocacy. Note that the newsletter is not thoroughly vetted by other staff and does not necessarily represent consensus views of Open Philanthropy as a whole.

Europe has enacted more farm animal welfare reforms than anywhere else in the world:

-

In 1976, the then-18 nations in the Council of Europe signed the world’s first convention on farm animal welfare, pledging to meet farm animals’ “physiological and ethological needs” and spare them “unnecessary suffering or injury.”

-

In 1997, European Union (EU) member states recognized the interests of “animals as sentient beings,” in a special protocol to the Treaty of Amsterdam.

-

From 1997 to 2001, the EU enacted partial bans on veal crates, gestation crates, and battery cages. These bans took effect between 2008 and 2013, benefiting an estimated 6M calves, 12M sows, and 370M hens per year across EU member states.

-

From 2002 to 2005, the EU helped secured the first animal welfare clause in a trade agreement, the first intergovernmental animal welfare conference, and the first global animal welfare standards, issued by the World Organisation for Animal Health.

But in the decade since, the EU has done little new to protect farm animals, even as American states and corporations have adopted more progressive animal welfare policies.

| A Comparison of EU and US Farm Animal Welfare Progress | ||

| EU | US | |

| Veal calves: crates banned after first 8 weeks (veal calves typically live 16-20 weeks).

Cows: no EU directives on dairy cow or beef cattle welfare beyond cross-species slaughter, transport, and husbandry regulations. |

|

Veal calves: crates banned in 7 states. Industry says 85% of veal calves are now crate-free, and 100% will be by end of this year.

Cows: no federal regulation outside of transport and slaughter. Dairy industry says it stopped tail docking this year. |

| Sows: gestation crates banned except during first 4 weeks and last week of sow’s roughly 16-week pregnancy. Farrowing crates used for the 2-4 weeks the sow weans her piglets.

Grower pigs: min. space requirement of 1-1.64 sq. m per pig. Transport and slaughter regulated. |

|

Sows: gestation crates banned in 10 states, otherwise legal. 70 US food companies say they’ll be crate-free by 2022; 15-20% of US sows are now crate-free. Farrowing crates prevalent.

Grower pigs: no state or federal regulation outside of transport and slaughter, nor corporate commitments. |

| Layer hens: battery cages banned, but enriched cages allowed with min. requirements of 116 sq. inches per caged bird, perches, litter, and a nesting box. About 40% of EU hens were cage-free as of 2011. |  |

Layer hens: cages banned in 5 states, otherwise legal. Industry min. space requirement of 67 sq. inches per caged bird. 14% of US hens are now cage-free, and 330 US food companies have pledged to be cage-free by 2026. |

| Broiler chickens: max stocking density of 33kg/sq. m – 42kg/sq. m, plus litter, lighting, living conditions, transport, and slaughter regulations. Breed and growth rates aren’t regulated. |  |

Broiler chickens: no state or federal regulation. ~4% of broilers are raised under credible welfare certification schemes. 45 US food companies have pledged reforms by 2024. |

So why did the EU lead on farm animal welfare, while the US lagged behind? I find three explanations most compelling:

- The focus of animal advocacy and animal welfare science: in a 2007 paper, Gaverick Matheny and Cheryl Leahy note that the US animal welfare movement arose later and initially focused less on farm animals than its European counterpart. They also note that America’s few animal welfare scientists have focused on maximizing productivity, whereas their more numerous European peers have focused on meeting animals’ ethological needs. And they point out that the US lacks anything akin to the European Commission’s Scientific Veterinary Committee, whose authoritative reports formed the basis for the EU’s bans on cages and crates.

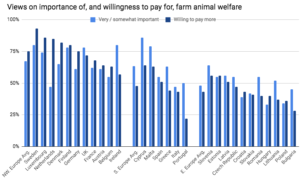

- Public awareness: Matheny and Leahy also point to a gap in public awareness of animal mistreatment. A 2003 Zogby poll commissioned by Brad Goldberg found that 71% of Americans agreed with the statement “in general, farm animals are fairly treated in the United States,” while a 2005 EU poll found that just 32% and 45% of Europeans thought that layer hens and pigs respectively had at least “fairly good” welfare. Awareness may explain the difference: the Zogby poll found that most Americans thought state laws already prohibited cruelty to farm animals, and thought it unacceptable when they found out these laws often don’t. And in a 2007 Oklahoma State poll, just 31% and 18% of respondents agreed that battery cages and gestation crates are humane.

- Political structure: America mostly regulates farm animal welfare at the state level, so most animals are at the mercy of farm states like Iowa; Europe mostly regulates at the EU-level, so higher-welfare states like Germany help set the standards for all animals. Almost all US state and federal animal welfare bills must start (and typically end) in hostile agriculture committees; most EU legislation starts in the technocratic European Commission. And should a bill ever reach the US Senate, it will face 32 US Senators who represent states with more than 6X as many farmed cows, pigs, and chickens as people; just one EU member state (the Netherlands) has such a ratio.

But these factors fail to explain why the trend stopped: why did the EU stop enacting major farm animal welfare reforms in the early 2000s? The factors above didn’t change: the successor to the EU’s Scientific Veterinary Committee continued producing technical reports after 2004 — on the welfare of farmed fish, rabbits, and other species. But whereas the European Commission or Parliament had previously issued legislation in response to most Committee reports, after 2004 they ceased doing so. Why?

The most obvious answer is that the Commission and Parliament changed. Northwestern European nations had always led the EU’s animal welfare efforts. The EU reforms gathered pace after Austria, Finland, and Sweden’s entry into the EU in 1995 created a clear majority of Northwestern nations. Germany pushed the EU’s battery cage ban during its 1999 Presidency of the EU Council of Ministers, assisted by the Austrian serving as the EU’s Commissioner for Agriculture at the time. Meanwhile two groups based in Northern Europe, Compassion in World Farming (UK) and Eurogroup for Animals (Belgium), lobbied the Southern European holdouts — France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain — to drop their opposition to the ban.

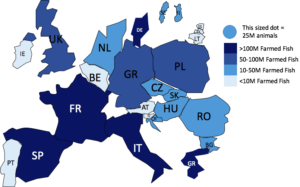

That dynamic changed in 2004, when ten new Eastern and Southern European nations joined the EU, creating a majority of member states opposed to reform. The 2005 EU poll found the residents of new member states much less concerned about farm animal welfare than their European neighbors: 21% of Czechs said they sometimes or always considered animal welfare when buying meat, whereas 67% of Swedes said they did. The difference persists in opinions (see 2016 poll below) and practices: fewer than 10% of Austrian and Dutch hens were caged as of 2011, while more than 90% of Estonian, Greek, Portuguese, and Spanish hens were.

I’m optimistic though that the EU will soon resume its leadership on farm animal welfare, for several reasons:

-

Movement growth: animal advocacy groups have grown much stronger in previously neglected Eastern and Southern European nations. For instance, consider France, Italy, Poland, and Spain, which collectively account for 46% of Europe’s farm animals. Animal Equality has held major street protests in Spain and gained over 300K online followers in Italy; Otwarte Klatki has secured the first Polish animal welfare pledges and gained almost 200K online followers in Poland; and L214 has secured cage-free pledges from all major French retailers and gained over 600K online followers in France.

-

Corporate progress: in the last year US-style corporate campaigns have generated cage-free pledges from about 50 European food companies. Although most to date have been British or German companies, French, Italian, Spanish, and Polish companies have all made pledges too. The more that corporate progress raises standards across Europe, the less resistance member states will likely show to the EU codifying these standards.

-

Brexit: while the UK has long had stronger animal welfare protections than other European countries, in recent years it has led the pushback against the EU regulatory state. With the UK on the way out, Germany and other Northwestern European nations will hopefully feel empowered to advance farm animal welfare regulations again.

Next month I’ll explore some ways we can address the elephant (or chicken) in the room: the world’s growing demand for animal products. In the meantime, I hope to see some of you at the National AR Conference this weekend — please come say hi!