This post originally appeared in the monthly farm animal welfare newsletter written by Lewis Bollard, program officer for farm animal welfare. Sign up here to receive an email each month with Lewis’ research and insights into farm animal advocacy. Note that the newsletter is not thoroughly vetted by other staff and does not necessarily represent consensus views of Open Philanthropy as a whole.

My colleague Abhi Kumar contributed research for this piece.

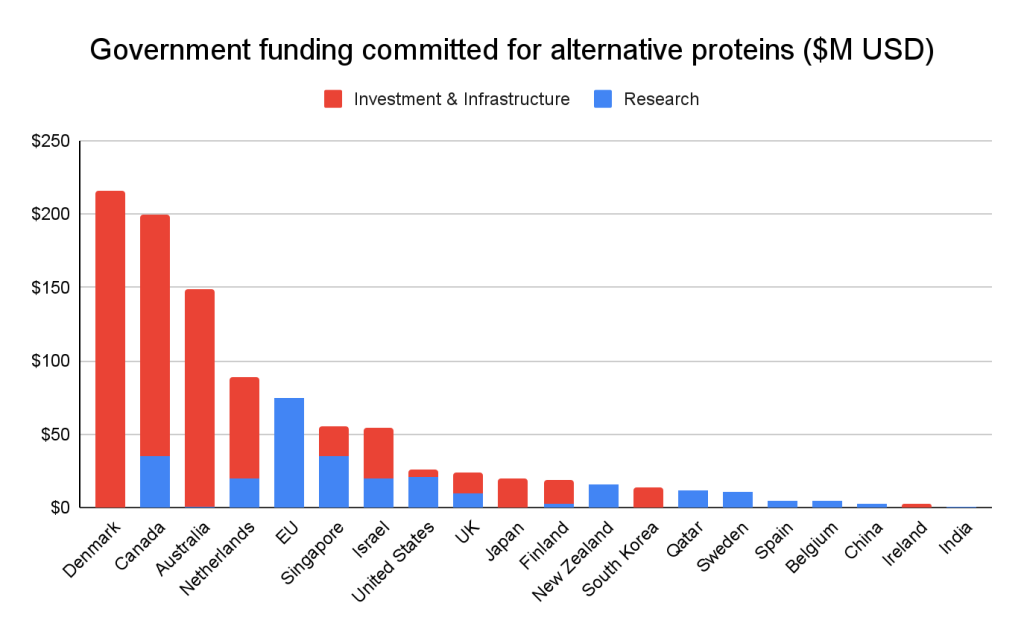

The Netherlands is promising €60M to build a cellular agriculture infrastructure. Australia is investing $113M to “supercharge Australia’s place in the global plant-based food value chain.” Denmark is allocating $175M to research, develop, and produce plant-based foods. Canada, Singapore, and Israel are all funding similar initiatives.

We estimate that the world’s governments have now committed almost a billion dollars to alternative protein research, infrastructure, and startups (see chart below). They’ve committed most of this funding in just the last three years.

The world’s biggest governments may soon spend more. China wants to “develop new foods such as ‘artificial protein’,” per its new Bioeconomy five year plan and comments from President Xi. The US will support “foods made with cultured animal cells” through its new Biotechnology initiative, according to a White House briefing. And the European Union sees “increasing the availability and source of alternative proteins” as a “key area of research” under its €10B agricultural research agenda.

What’s going? Three great new reports — from the Good Food Institute, FAIRR, and Emerging Proteins NZ — identify three main forces at work. Food security seems to be motivating countries without much farmland, like Singapore, Israel, and Qatar. The opportunity to profit from growing the crops used in plant proteins seems to be motivating countries with lots of farmland, like Australia and Canada. And climate concerns seem to be motivating politically progressive countries, especially in Europe.

So what can we do to accelerate and direct this trend? But, first, why do we need government support in the first place?

Governments have now committed almost a billion dollars to investments, infrastructure, and research to advance plant-based, fermented, and cultivated alternatives to animal products. Sources: our estimates based on GFI, FAIRR, Emerging Proteins NZ, and independent research.

Alternative Financing

Until recently, it seemed like alternative proteins might not need government aid. The space was awash with cash, thanks to billions in sales, the heft of the world’s largest food multinationals, and almost $10B in private investments.

But markets are fickle. Plant-based meat sales are down: by 5% in US retail over the last year and possibly more globally — Beyond Meat’s international sales last quarter were about half what they were in the same quarter last year. (Why? I recommend Michal Klar’s analysis.) Some food multinationals are retreating: JBS recently shuttered its US plant-based meat arm, while Maple Leaf Foods, owner of Lightlife and Field Roast, cut 25% of its plant-protein division. (Nestle and Unilever are notable exceptions.) And investors, including the “impact” variety, are newly hesitant to invest.

Governments can’t solve this downturn, but they can increase the odds of alternative proteins’ future success. In particular, they can help solve three of alternative proteins’ biggest challenges:

-

Cost. Plant-based meat is pricey: in the US, it retails for about twice the price of other meat; elsewhere, it’s even dearer. That matters: studies suggest that demand for plant-based meat is much more sensitive to prices than demand for other meat. Startups are making progress — US plant-based meat prices rose just 1.4% over the last year, much slower than inflation — but not yet enough. Governments could drive down prices through tax incentives, public procurement, and subsidized loans.

-

Quality. The best plant-based meats still aren’t good enough: in a recent blind taste test of 86 students, a beef burger easily beat out the Beyond and Impossible burgers. The cheapest plant-based meats are often worse — Tesco’s Plant Chef range recently hit price parity with meat, but reviews suggest some customers view it as a closer substitute for cardboard than meat. Governments could improve quality by funding open access research beyond the timelines and risk tolerance of private investors.

-

Infrastructure. The profusion of plant-based meat brands — at least 60 in US retail alone — hides the industry’s reliance on a handful of co-manufacturing facilities, most of which were built to process meat. This prevents specialization and makes the industry vulnerable to supply shocks. Meanwhile, the cultured meat and fermentation industries need to build biomanufacturing capacity almost from scratch. Governments could help by building large-scale infrastructure, as Australia, Canada, and Denmark are doing.

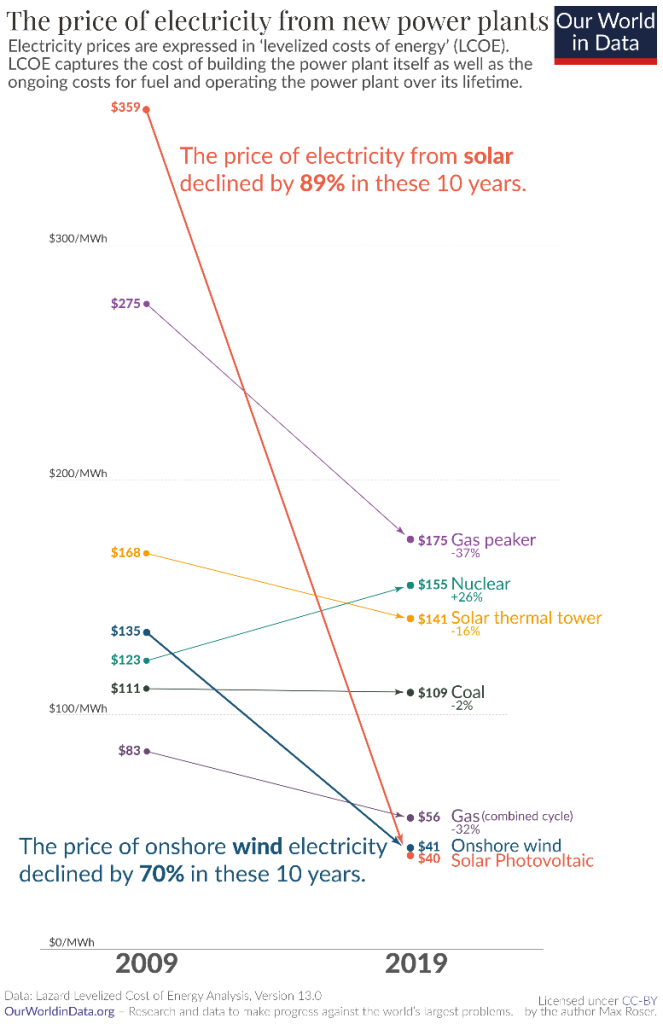

There’s precedent for governments doing all this on a large scale. Clean energy, electric vehicles, and batteries have each seen steep price declines and quality improvements over the last decade, partly thanks to government investments in research, tax incentives, and infrastructure. Those investments were huge: the American Recovery Act of 2009 alone poured $90B into clean energy, including renewables and electric vehicles, while China likely invested much more over the following decade.

Solar and wind electricity prices declined by 89% and 70% respectively in one decade, thanks partly to government support. Note: past alternative energy results do not predict future alternative protein performance. Source: Our World in Data.

Cultivating Government Support

Advocates are well-positioned to accelerate this trend. As we try to, I think it’s worth keeping a few principles in mind:

-

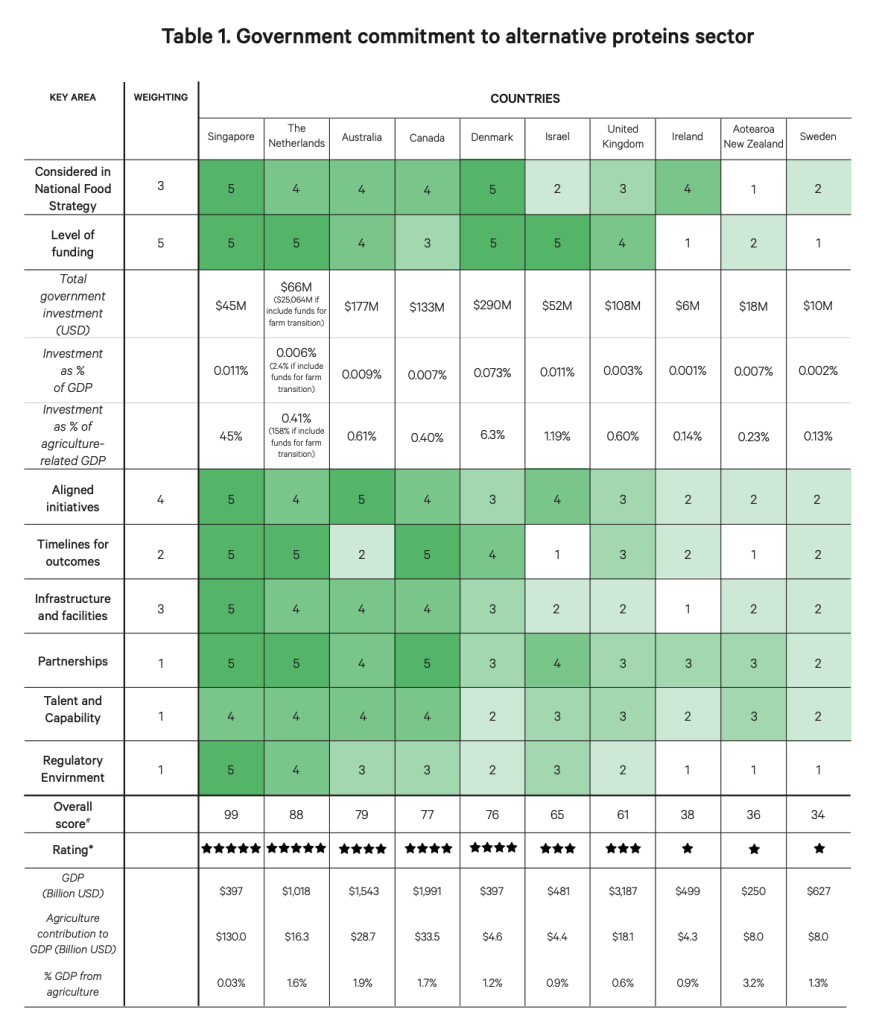

Governments can help in lots of ways. The Emerging Proteins NZ report outlines the many tools at governments’ disposal, from research grants and scholarships, to tax incentives, regulatory reform, and subsidized or guaranteed loans. (See chart below.) Clean energy technologies also benefited from novel instruments like milestone payments, buyers’ clubs, and advance market commitments.

-

Some government help is much more valuable. GFI credits Singapore and Israel (only #6 and #7 in the funding chart above) with the most impactful government policies. That’s because they’ve paired targeted research funding with comprehensive support for the sector — with great success: the two tiny countries now account for a considerable share of the world’s alternative protein startups.

-

Insects aren’t alternative proteins. Insect farming isn’t an alternative to factory farming; it’s a supplier. It’s also a potential moral catastrophe: the industry already raises over a trillion insects annually, with little concern for their welfare, despite increasing evidence that they may be sentient. Yet insect farmers have secured their inclusion in many alternative protein funding schemes, like the EU’s. Reversing this trend should be a top priority for advocates working on the issue.

You can help. You can ask your political representatives and government agencies to support alternative proteins. If you’re a political donor or volunteer, your voice may be especially influential — US political donors may also want to reach out to Food Solutions Action. You can support initiatives campaigning for government support. Together we can hopefully make alternative proteins the next alternative energy, so that one day the “alternative” becomes the default.

It’s not just about the money: Singapore and the Netherlands lead a recent Emerging Proteins NZ ranking of government support for alternative proteins. As a New Zealander, I’m proud that a New Zealand government-funded entity produced a report that ranks New Zealand second-to-last. Source: Emerging Proteins NZ.