This is a writeup of a shallow investigation, a brief look at an area that we use to decide how to prioritize further research.

In a nutshell

What is the problem?

Nuclear risks range in magnitude from an accident at a nuclear power plant to an individual detonation to a regional or global nuclear war. Our investigation has focused on the risks from nuclear war, which, while unlikely, would have a catastrophic global impact.

What are possible interventions?

A philanthropist could fund research or advocacy aimed at reducing nuclear arsenals, preventing nuclear proliferation, securing nuclear materials from terrorists, or attempting to more directly prevent the use of nuclear weapons in a conflict (e.g. by working with civil society actors to reduce the risk of conflict). A funder could also raise awareness about risks from nuclear weapons in general by working with media or educators, or through grassroots advocacy.

Who else is working on it?

Several major U.S. foundations fund approximately $30 million/year of work on nuclear weapons issues, with most of this work supporting U.S.-based policy research and graduate/post-graduate education, some advocacy, and “track II diplomacy” (i.e. meetings between nuclear policy analysts and current and former government officials, often from different states). We do not have an estimate of funding from other non-profits in the space, but the Nuclear Threat Initiative has an annual budget of $17-18 million and is not primarily funded by foundations. The U.S., other governments, and the International Atomic Energy Agency spend much larger amounts of money managing risks from nuclear weapons. We see work on nuclear weapons policy outside of the U.S. and U.S.-based advocacy as the largest potential gaps in the field, with the former gap being larger, but also harder for a U.S.-based philanthropist to fill.

1. What is the problem?

1.1 Our focus on nuclear war

There are numerous conceivable scenarios in which some sort of nuclear incident could occur, ranging from a meltdown at a nuclear power plant to the detonation of a “dirty bomb” (i.e. a bomb that combines radioactive material with conventional explosives) to an outright nuclear war between states.1< Though this is not a question we have thoroughly investigated, the risk of nuclear war between states strikes us as the most potentially destructive scenario because of the magnitude of some states’ nuclear arsenals, the possibility of wider escalation, and the possibility of nuclear winter. Accordingly, although we recognize the devastating potential of other kinds of nuclear incidents, our discussion below focuses on the risk from nuclear war.2 Note that we interpret efforts to address the risk of nuclear war broadly, to include issues like reduction of nuclear arsenals, prevention of nuclear proliferation, securing nuclear materials, and facilitating domestic civil discourse regarding nuclear weapons among countries that may seek to acquire nuclear weapons.

The U.S. and Russia hold the vast majority of the world’s nuclear weapons:3

| COUNTRY | ESTIMATED NUCLEAR WEAPONS INVENTORY |

|---|---|

| Russia | 8,000 (4,300 in military custody) |

| United States | 7,300 (4,760 in military stockpile, 1,980 deployed) |

| France | 300 |

| China | 250 |

| Britain | 225 |

| Pakistan | 100-120 |

| India | 90-110 |

| Israel | 80 |

| North Korea | <10 |

| Total | ~16,300 |

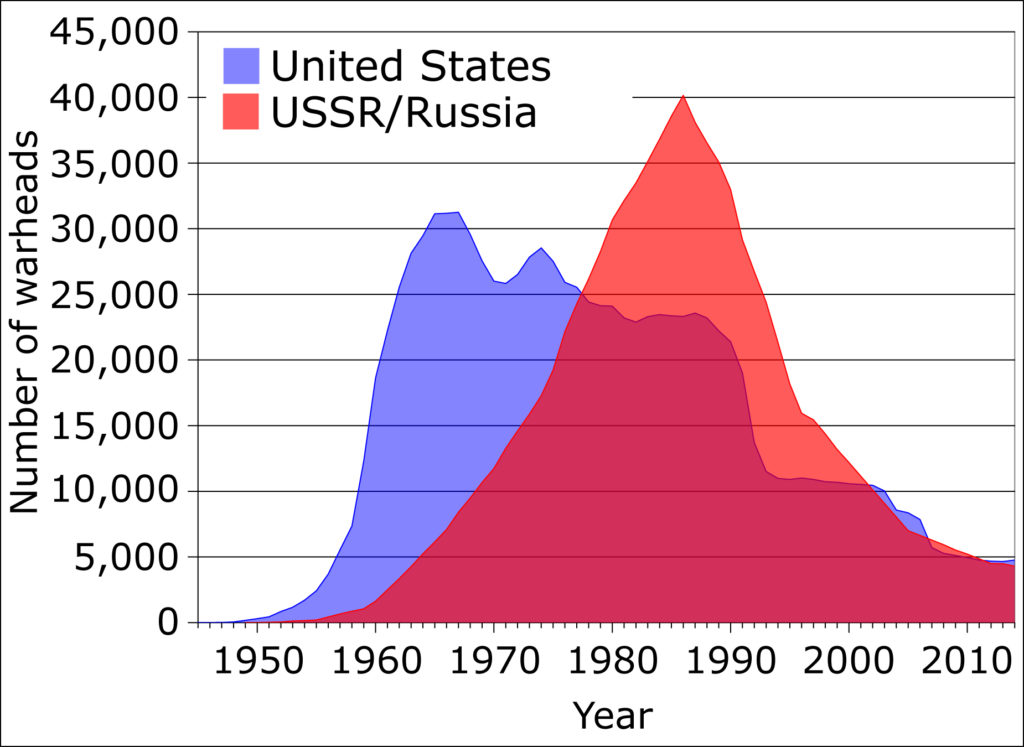

Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. and Russia nuclear weapons inventories have greatly (and fairly continuously) declined, as illustrated by the graph below:4

We have not thoroughly investigated the probability or likely consequences of a nuclear detonation or a broader nuclear war, though we see both scenarios as possibilities. Our understanding is that the risk of global nuclear escalation has decreased substantially since the end of the Cold War.5 We note, however, that some people we spoke with suggested that total nuclear risk had increased since the Cold War.6

1.2 Which conflicts are most worrisome?

Though very unlikely in the present climate, a nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia would have the greatest destructive potential. A 1979 report by the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment estimated that in an all-out nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia, 35-77% of the U.S. population and 20-40% of the Russian population would die within the first 30 days of the attack.7 We have not vetted this estimate, but note that at the time, combined U.S./Russia nuclear weapons stockpiles were approximately three times as large as they are today, as seen in the graph above. An additional potential risk of a U.S./Russia nuclear would be the nuclear winter that might follow. Nuclear winter could potentially disrupt global food production and result in an even larger number of deaths, though we have not thoroughly explored the likelihood or likely consequences of this scenario.

People we spoke with generally perceived the greatest risk of nuclear conflict in South Asia, where Pakistan has pledged to respond to any Indian attack on its territory with a nuclear bomb.8 Some scholars have argued that a war between India and Pakistan could alter the global climate, potentially threatening up to a billion people with starvation,9 though this estimate strikes us as high. Our understanding is that this claim is primarily based on:

- Modeling the amount of smoke that would reach the stratosphere in the event of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan in which 100 nuclear weapons strike cities.10

- Using a climate model to simulate the effect of that smoke going into the stratosphere.11

- Using a crop model to estimate the effect of those climactic changes on the yields of crops in China and the Midwest.12

The last paper cited estimated that a 100-weapon nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan would result in a 10% decline in average caloric intake in China, with potentially similar consequences elsewhere.13

We have not vetted this analysis. However, even accepting its conclusions, our impression is that relatively little work has been done to consider the likely human consequences of the subsequent decline in agricultural production.14 We would guess that the predicted loss of crops would be insufficient to cause a billion people to starve for the following reasons:

- China has significant food reserves, which, according to the paper estimating changes in the yields of crops cited above, would not be depleted until two years after the initial nuclear exchange.15

- Our impression is that the crop model was not designed with extreme scenarios like this in mind, and is not accounting for pressure to make significant changes to food production in the midst of a global crisis.

- A substantial portion of crops grown are used to feed livestock, which is significantly less efficient than slaughtering existing livestock and directly eating the food we normally use to raise them. In the short run, livestock reserves could be slaughtered to meet demand for food.16 In the longer run, we would guess that a decrease in the food supply would raise food prices, creating incentives to produce more food (e.g. by using more land for food production and shifting away from less efficient animal-based means of production).

2. What are possible interventions?

2.1 Areas for nuclear policy work

Almost any kind of progress on nuclear security ultimately requires some kind of change on the part of government, or the prevention of some change. Accordingly, much of the grant-making in this field focuses on:

- Policy analysis by think tanks and university centers focused on nuclear weapons issues.

- Advanced education to create better policy analysis in the future, such as support for academic centers that provide graduate and post-doctoral training in the field of nuclear weapons policy.17

- Advocacy and communications, which is a major focus of the Ploughshares Fund (discussed below).

- Track II diplomacy—meetings between nuclear policy analysts and current and former government officials, often from different states.

George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, identified several different goals for this work:18

- Reduction of nuclear arsenals

- Prevention of nuclear proliferation

- Preventing terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons

- Direct efforts to prevent nuclear escalation

Additionally, work can be categorized by the region the topic relates to (e.g. policy related to Iran, Russia, South Asia, North Korea, United States) and where the work is done (e.g. is the scholar/advocate working in the U.S. or India?).

2.1.1 Reduction of existing nuclear arsenals

Work to reduce nuclear arsenals typically focuses on the five permanent members of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which possess the largest numbers of nuclear weapons. Several approaches have been proposed for encouraging these countries to reduce their nuclear arsenals:

- Laying the intellectual groundwork for further talks between the U.S. and Russia about reducing the number of warheads in each country’s stockpile

- Advocating for the U.S. executive branch to reduce the U.S. nuclear stockpile19

- Supporting policy research and advocacy related to ballistic missile defense. Russia and China are concerned that U.S. investment in ballistic missile defense—i.e. systems for shooting down incoming ballistic missiles—could destabilize deterrence relationships. If ballistic missile defense were sufficiently effective, it could increase the number of nuclear weapons needed to ensure successful retaliation. Accordingly, U.S. investment in this area poses a potential obstacle to negotiating further arms reductions in Russia and China.20

Some organizations, such as Global Zero, advocate for the elimination of all nuclear weapons. We have not investigated the question of whether outright elimination is likely to be the best policy path, but we understand this to be an area of active debate within the academic community.21

The Ploughshares Fund is the largest funder of advocacy efforts with an annual budget of approximately eight million dollars. It argues in favor of cutting the U.S. federal budget for nuclear weapons.22 Joe Cirincione (President, Ploughshares Fund) and Philip Yun (Executive Director, Ploughshares Fund) identified the following advocacy opportunities for reducing the size of nuclear stockpiles in the U.S.:

- Promoting public support for the ideas that nuclear weapons continue to pose significant risks, have limited deterrence value, and are costly to maintain. A philanthropist could seek to build support for these ideas by working with filmmakers or improving online educational materials and social media campaigns.

- Supporting efforts to revive the U.S.-Russia dialogue on nuclear weapons.

- Seeking to influence the nuclear policy of the next presidential candidates by supporting relevant policy analysis.23

- Advocating for lawmakers to reduce the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

- Supporting policy analysis and advocacy opposing the development of ballistic missile defense in the U.S. in hopes of making U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China mutual arms reductions more likely (discussed above).

While arms reductions in the U.S. and Russia may appear to be a natural target for a funder interested in reducing global catastrophic risk, we are uncertain about how much additional philanthropy could assist with arms reduction at this time. As noted above, the U.S./Russia weapons inventories have steadily declined since the end of the Cold War, suggesting that progress on the problem may continue in the absence of additional philanthropy. In addition, people we spoke with and consultants surveying the field for other funders saw limited opportunities for additional philanthropy to push forward U.S./Russia arms reductions.24

2.1.2 Prevention of nuclear proliferation

Non-proliferation work is focused on preventing additional countries from obtaining nuclear weapons. Within non-proliferation, the most common concern among people we spoke with was that Iran might obtain a nuclear weapon. For example, Joe Cirincione suggested that a philanthropist could advocate in favor of making a deal with Iran that would prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons,25 which is a major focus for the Ploughshares Fund (see “Philanthropic Funders” below). If Iran obtains nuclear weapons, it could potentially destabilize the Middle East and encourage other countries to obtain nuclear weapons.26 In early 2015, after most of this review was already written, the U.S. and Iran reached an agreement on a framework for monitoring Iran’s nuclear program, though the deal has not yet been approved. We have a limited understanding of how this might affect philanthropic approaches related to non-proliferation in Iran.27

Some funders appear to focus on advocacy to individual countries that may attempt to acquire nuclear weapons, or on funding academic and civil discourse related to nuclear weapons in key regions through non-nuclear states such as Turkey, Brazil and South Korea.28 Others focus more on supporting international institutions such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).29 Carl Robichaud—a Program Officer focusing on the International Peace and Security Program at the Carnegie Corporation of New York—identified the following options for a philanthropist to support the IAEA:30

- Fund open source analysis on topics that would be of use to the IAEA

- Hold workshops where IAEA staff can learn how to utilize new tools and approaches, such as geospatial analytics and big data analysis (the Carnegie Corporation put on a workshop between IAEA staff and innovators from other sectors in December)

- Support the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, which serves as research and training center for the IAEA

- Sponsor dialogues within the IAEA to reduce politicization

2.1.3 Preventing terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons

Another approach would be to support appropriate monitoring of existing nuclear material in an attempt to prevent it from falling into the hands of terrorists. The difficulty and high costs of manufacturing nuclear weapons makes securing nuclear materials important for preventing nuclear terrorism.31 The Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) has been addressing this problem by using the Nuclear Security Summits to develop buy-in for global, enforceable nuclear security standards, which currently don’t exist.32

A nuclear terrorist attack is not a nuclear war and therefore not directly in the center of this investigation, but we would guess that nuclear terrorism—particularly in South Asia—could potentially ignite a nuclear war. A philanthropist could try to prevent terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons through:

- Policy development and advocacy related to creating a standard set of international norms regarding the security of nuclear materials.33

- Funding innovative demonstration projects in hopes of causing governments to scale them up. For example, Joan Rohlfing —President and COO of NTI—told us that the Nuclear Threat Initiative worked with Serbia to return non-secure nuclear materials to Russia, and that the effort led to the creation of a U.S. government program that spent billions of dollars on similar projects.34

Our impression is that the security of nuclear materials already receives significant attention. It is the primary focus of the Nuclear Threat Initiative,35 and a priority for national governments.36

2.1.4 Direct efforts to prevent nuclear war

Direct efforts to prevent nuclear war may focus on attempting to reduce the likelihood of deployment of nuclear weapons in a given conflict situation, or on attempting to reduce the risk of conflict between nuclear states. In our conversation, Dr. Perkovich gave some examples of both kinds of efforts with respect to India and Pakistan, focusing on various forms of civil society engagement, “track II” diplomacy, and policy research.37

We have not thoroughly explored this area, but people we spoke with have suggested there may be limited potential for additional philanthropy to address these issues, at least in Russia (as discussed above) and in South Asia.38

2.2 Approaches to improving nuclear weapons policy and their track records

2.2.1 Policy analysis and advanced education

A majority of funding supports policy research and advanced education, especially from the large foundations in this space.39 However, we have a fairly limited sense of the track record of policy analysis for improving nuclear weapons policy. Nevertheless, we understand that funding from the Carnegie Corporation and the MacArthur Foundation is generally believed to have played a major role in the passage of the Nunn-Lugar Act40, which was responsible for “the dismantling or elimination of 7,514 nuclear war-heads, 768 ICBMs, 498 ICBM sites, 155 bombers, 651 submarine-launched ballistic missiles, 32 nuclear submarines, and 960 metric tons of chemical weapons.”41 For context, according to one estimate, the U.S. and Russia held 19,008 and 29,154 nuclear weapons (respectively) when the Nunn-Lugar Act was passed in 1991, so that Nunn-Lugar was responsible for eliminating or dismantling approximately 15% of the total U.S./Russia nuclear arsenal.42

Policy research funded by philanthropists may have played a role in improving nuclear policy in a few other cases besides the Nunn-Lugar Act—such as establishing theories of deterrence and the New START treaty, which further reduced deployed warheads in the U.S. and Russia.43

Due to our limited understanding of nuclear weapons policy analysis, we also have a limited understanding of the potential impact of advanced education on nuclear weapons policy.

2.2.2 Advocacy

Multiple people suggested to us that work on advocacy and communications is relatively neglected in nuclear weapons policy.44 Our investigation therefore focused more closely on opportunities within advocacy.

In addition to the advocacy opportunities already mentioned (especially under the heading “Reduction of existing nuclear arsenals”), building general capacity for advocacy in order to change policy if a window of opportunity arises may be valuable.45

We are uncertain about the role for grassroots advocacy on nuclear weapons issues, in comparison with more technocratically-oriented advocacy and policy analysis. On this topic:

- Robert Einhorn—a senior fellow with the Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Initiative and the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at the Brookings Institution—cautioned that grassroots efforts have a mixed record at best in changing nuclear policy, pointing to the fact that the U.S. has not ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty despite its support from a large majority of Americans.46

- Mr. Robichaud pointed to the New START treaty as an instance where public engagement played an important role.47

2.3 Philanthropic opportunities in other countries

Very little foundation funding supports nuclear policy work abroad, which means that other countries have much more limited capacity for developing and advocating for policy related to nuclear weapons,48 though U.S. foundations have funded some policy research in Russia and Asia:

- The MacArthur Foundation’s Asia Security Initiative supported increased communication and dialogue between policy analysts working on security issues relevant to Asia, including supporting researchers in Asia. This program has since ended.49

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has a satellite center in Moscow, and it has received funding from the Carnegie Corporation.50

A philanthropist looking to further support opportunities in other countries could:

- Fund the creation of a center for nuclear policy research in Pakistan in hopes of increasing Pakistan’s willingness to comply with international nuclear law and norms.51

- Fund fellows programs for people from Asia, perhaps including an exchange component during which the fellows spend time at U.S. or U.K. institutions, to train the next generation of nuclear policy analysts.52

- Fund professors/senior researchers from U.S. nuclear policy institutions to visit think tanks in Asia and help train young nuclear policy analysts.53

However, people we spoke with suggested it would be challenging for a foundation to make its first grants on nuclear weapons policy in support of programs abroad54 and stressed the importance of having a local presence for monitoring grants.55 Our impression is that a philanthropist supporting research, education, and/or advocacy abroad would face significant challenges in terms of networking, communication, understanding context, and monitoring/evaluation.

We distinguish between work done in other countries and work about the policies of other countries. While the former receives limited attention, the latter does not, and has been discussed in various contexts above. For example, work related to potential conflict in South Asia—where the greatest threat is perceived56—is relatively crowded. Nuclear issues in South Asia receive substantial attention in the form of programs at universities and think tanks57 as well as track II diplomacy, and some funders see little room for additional philanthropy on the topic.58

3. Who else is working on this?

3.1 Government

According to Gary Samore, Executive Director for Research at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard:59

Nearly all government security agencies are involved with nuclear policy to some degree, including:

- The White House International Security Council

- The Department of Defense

- The Department of State

- The Department of Energy, involved in both nuclear energy and nuclear security (through the National Nuclear Security Administration)

- Intelligence agencies

We have not investigated the amount of funding these agencies devote to nuclear issues and have a limited understanding of their activities. But some agencies with large budgets focus primarily on keeping people safe from nuclear weapons:

| AGENCY | BUDGET | ACTIVITIES |

|---|---|---|

| National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) | $12.6B, of which $1.9B is categorized as non-proliferation.60 | “NNSA maintains and enhances the safety, security, reliability and performance of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile without nuclear testing; works to reduce global danger from weapons of mass destruction; provides the U.S. Navy with safe and effective nuclear propulsion; and responds to nuclear and radiological emergencies in the U.S. and abroad.”61 |

| Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO) | $304M62 | The DNDO coordinates U.S. government efforts to detect and prevent nuclear and radiological terrorism against the United States.63 |

In addition, some intergovernmental organizations devote substantial funding to nuclear security issues. For example, in 2014, the International Atomic Energy Agency had a budget of €344M.64

We currently have a very limited understanding of the activities of these U.S. government agencies and the IAEA. However, our understanding is that the government provides at most limited support for the primary areas addressed by philanthropic funders, such as policy development, advanced education, advocacy, and track II diplomacy.65

3.2 Philanthropic funders

A 2012 report by Redstone Strategy Group, commissioned by the Hewlett Foundation, estimated that philanthropic funding for work on nuclear security between 2010 and 2012 was $31 million/year.66

Our impression is that the total funding in the field has not substantially changed, though some funders have exited the field. A few foundations account for the vast majority of this funding.

| FUNDER | BUDGET (2014 ESTIMATE) | FOCUS AREAS |

|---|---|---|

| MacArthur Foundation | ~$10M67 | Policy research and advanced education in the U.S., focused on control of fissile materials and preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to terrorists.68 |

| Carnegie Corporation of New York | ~$10M69 | Policy research, advanced education in the U.S., track II diplomacy. Focused on arms reductions, non-proliferation, and security of nuclear materials.70 |

| Ploughshares Fund | ~$8M, ~$5.5M in grants | Advocacy, especially U.S. policy towards Iran and the U.S. nuclear budget.71 |

| Hewlett Foundation | Previously $4M (2012 estimate),72 exiting the field.73 | Security of nuclear materials and reducing nuclear arsenals.74 Hewlett’s largest grants in this field were to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Ploughshares Fund.75 |

| Sloan Foundation | Previously $2.9 million (2012 estimate),76 exited the field.77 | Policy research and advanced education.78 |

| Skoll Global Threats Fund | $1-2M | Advocacy, especially U.S. policy toward Iran. Ploughshares is a major grantee.79 |

| Stanton Foundation | $2.3M (2012 estimate)80 | Advanced education and policy research in the U.S.81 |

There are also some nonprofits that work on nuclear security issues that do not receive most of their funding from foundations, including, most notably, the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), whose 2015 budget is about $17-18M. Of this, about 90% is devoted to nuclear weapons and about 30% is granted to other organizations (though NTI’s grants usually resemble contracts for service with partners who carry out specific projects that NTI has designed).82 Within nuclear weapons policy, NTI primarily emphasizes securing nuclear materials in order to prevent terrorism, with non-proliferation as a secondary emphasis.83 We do not have an overall accounting of activity by other nonprofits in this area, but a list of the top grant recipients in peace and security in 2008-2009 is available in a report by the Peace and Security Funders Group.84 We would guess that many of the major nonprofits working on nuclear weapons policy are listed there.

Foundations also provide substantial funding for peace and security that isn’t explicitly classified as work on nuclear weapons policy. According to the Peace and Security Funders Group, in 2008-2009, 91 U.S. foundations gave a total of $257M to promote peace and security, for an average of about $130M per year.85 The largest focus areas for these funders (measured by dollars granted) were:

- Controlling and Eliminating Weaponry (which is described as “mainly focused on nuclear weapons”)

- Prevention and Resolution of Violent Conflict

- Promoting International Security and Stability

Each of these areas received about 20-30% of the total funding.86

3.3 Crowdedness of different philanthropic approaches

This section primarily organizes information presented above in order to summarize relative crowdedness of different areas of work on nuclear weapons policy.

The largest potential gaps in this space appear to be work on nuclear weapons policy outside of the U.S. and U.S.-based advocacy, with the former gap being larger but harder for a U.S.-based philanthropist to fill.

As mentioned above, very little foundation funding supports nuclear policy work abroad, which means that other countries have much more limited capacity for developing and advocating for policy related to nuclear weapons.87 However, foundations have funded some work in this area:

- The MacArthur Foundation’s Asia Security Initiative supported increased communication and dialogue between policy analysts working on security issues relevant to Asia, including supporting researchers in Asia. This program has since ended.88

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has a satellite center in Moscow, and it has received funding from the Carnegie Corporation.89

A majority of funding supports policy research and advanced education, especially from the large foundations in this space.90 The Ploughshares Fund is the largest foundation focused primarily on advocacy, and is spending about $8M per year. Multiple people suggested to us that work on advocacy and communications were relatively neglected in nuclear weapons policy.91

We have a more limited sense of which areas are most crowded in terms of regional focus (e.g. Iran, Russia, South Asia, North Korea, United States) or objective pursued (e.g. preventing new states from getting nuclear weapons, decreasing the number of nuclear weapons held by countries that already have them, or securing nuclear materials to prevent terrorists from gaining access to them). However, our impression is that work related to potential conflict in South Asia—where the greatest threat is perceived92—is relatively crowded. Nuclear issues in South Asia receive substantial attention in the form of programs at universities and think tanks93 as well as track II diplomacy, and some funders see little room for additional philanthropy on the topic.94 We also note that in early 2015, the U.S. and Iran reached an agreement on a framework for monitoring Iran’s nuclear program, though we have a limited understanding of how this might affect philanthropic approaches related to non-proliferation in Iran.95

Our impression is that the security of nuclear materials also receives significant attention. It is the primary focus of the Nuclear Threat Initiative,96 and a priority for national governments.97

4. Questions for further investigation

We have not deeply explored this field, and many important questions remain unanswered by our investigation.

Amongst other topics, our further research on this cause might address:

- What are the options for a funder seeking to support work on nuclear weapons policy abroad, particularly in Russia or South Asia? What comparable work has been done in the past, and what is its track record?

- What other advocacy-based approaches could be pursued within nuclear weapons policy?

- What other strategies are there for reducing U.S./Russia nuclear inventories? Have we missed any particularly promising strategies that are not being pursued as aggressively as they could be? How would the potential severity of a nuclear winter decline as nuclear inventories shrink?

- What are the areas where policy research might lead to improved policy? What does such work typically involve? How has policy research in this field resulted in policy change in the past? Are any areas particularly neglected?

- To what extent could work normally classified under “international peace and security” but not “nuclear weapons policy” or “nuclear security” contribute to reducing the risk of a nuclear war?

- How likely is the detonation of a nuclear weapon or a broader nuclear escalation? Which sources or conflicts contribute the most to these risks?

5. Our process

We initially decided to investigate the cause of nuclear safety because:

- The potential devastation from the use of nuclear weapons is so great that an investment in nuclear safety could conceptually have high returns.

- Unlike some other global catastrophic risks, there is an established philanthropic community working to address nuclear safety issues.

We spoke with 12 individuals with knowledge of the field, including:

- Joe Cirincione, President, Ploughshares Fund

- Robert Einhorn, Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution

- Megan Garcia, Program Officer for the Hewlett Foundation’s Nuclear Security Initiative

- Erika Gregory, Founding Director, N Square: The Crossroads for Nuclear Security Innovation

- Bruce Lowry, Director of Policy and Communications, Skoll Global Threats Fund

- George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Carl Robichaud, Program Officer, International Peace and Security, Carnegie Corporation

- Joan Rohlfing, President and COO, Nuclear Threat Initiative

- Gary Samore, Executive Director for Research, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

- Philip Yun, Executive Director and COO, Ploughshares Fund

In addition to these conversations, we also reviewed documents that were shared with us and had some additional informal conversations.

Previous version of this page here.

6. Sources

| DOCUMENT | SOURCE |

|---|---|

| Carnegie Corporation Annual Report, 2013 | Source |

| Carnegie Corporation Nuclear Security Program Website | Source (archive) |

| Department of Homeland Security, Budget-in-Brief: FY 2015 | Source (archive) |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Bruce Lowry, November 5, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Carl Robichaud, October 14, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Erika Gregory, September 22, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Gary Samore, September 8, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with George Perkovich, June 6, 2013 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Joan Rohlfing, December 8, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Joe Cirincione, November 15, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Philip Yun, October 16, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Robert Einhorn, November 10, 2014 | Source |

| Hewlett Foundation Grants Database, 2015 | Source (archive) |

| Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Logic Model | Source |

| Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Webpage | Source (archive) |

| IAEA Regular Budget for 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Kristensen and Norris 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Kristensen and Norris 2014 | Source (archive) |

| MacArthur Foundation’s description of its nuclear security program, March 2014 | Source (archive) |

| MacArthur Foundation International Peace & Security Grant Guidelines, December 2014 | Source (archive) |

| National Nuclear Security Administration, About us | Source (archive) |

| National Nuclear Security Administration, Budget | Source (archive) |

| NTI 2012 Annual Report | Source (archive) |

| Nunn-Lugar Report for GiveWell’s History of Philanthropy Project by Benjamin Soskis, July 2013 (DOCX) | Source |

| Office of Technology Assessment 1979 | Source (archive) |

| Ploughshares Fund blog post | Source (archive) |

| Redstone Strategy Group 2012 | Source |

| Robock and Toon 2009 | Source (archive) |

| Robock et al. 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Shulman 2012 | Source (archive) |

| Stanton Foundation International and Nuclear Security Webpage | Source (archive) |

| Toon et al. 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Vox, Meet the political scientist who thinks the spread of nuclear weapons prevents war | Source (archive) |

| Vox, The Iran nuclear deal translated into plain English, April 2015 | Source (archive) |

| Wikimedia Commons, US and USSR nuclear stockpiles | Source |

| Xia et al. 2013 | Source (archive) |