Note: This writeup represents the state of our investigation into criminal justice reform as of May 2014, after some preliminary investigation. Since then, our views have changed noticeably, but they remain preliminary, and we have hired a Program Officer to lead our work in this cause going forward. If you have additional information on this cause that you feel we should consider, please feel free to get in touch.

In a nutshell

What is the state of our investigation into U.S. criminal justice reform?

We have completed our medium-depth investigation of criminal justice reform.1 The investigation has continued to progress and we have made some grants in this area. However, we have not yet chosen criminal justice reform (or any other cause) as a long-term program area. In order to learn substantially more from this investigation we believe that we would need to commit to this cause for the medium-term (i.e., several years), so we have paused this investigation until we are ready to select U.S. public policy causes for that level of commitment.

Why are we making criminal justice reform grants?

Criminal justice reform seems like a particularly promising area because (a) we have identified a set of people who are promoting a particular viewpoint that is both appealing to us and appears underfunded, meaning that finding initial promising giving opportunities took less work in this area than we’d expect it would in many others; and (b) as evidenced by a wave of reform packages in over twenty states and the recent confluence of conservative and progressive interest in reform, this issue seems to strongly stand out from most political issues in terms of political momentum and tractability.

What is the problem?

The United States incarcerates a larger proportion of its residents than almost any other country in the world and still has the highest level of criminal homicide in the developed world.2 While confounding factors impede rigorous analysis of incarceration’s effect on the crime rate, it has been argued (and seems probably correct) to us that, while initial increases in the incarceration rate may have reduced crime, a rate this high does not have large benefits for public safety and represents indiscriminate incarceration of offenders whether or not prison is the appropriate punishment. In particular, it seems plausible that the United States incarcerates too many low-risk offenders for too long. Incarceration has large fiscal costs. We believe that it also has large human and economic costs. Community corrections (such as probation and parole), which are one of the main alternatives to incarceration, may also need improvement, as evidenced by the 40% revocation rate for persons on probation.3

What are possible interventions?

Proposals for criminal justice reform can broadly be divided into two categories. Front-end reforms affect individuals at their first point of contact with the criminal justice system. Back-end reforms affect individuals after they have already entered the criminal justice system.

Strategies to promote these reforms include policy research, legislative advocacy, technical assistance to policymakers or practitioners, litigation, communication and public education, direct services, and pilot projects.

Criminal justice reform is a broad field and we have so far focused on the particular set of interventions that initially got us interested in this cause — interventions that broadly seek to reduce incarceration while having neutral or even positive effects on public safety, by focusing prison beds on higher-risk offenders and improving community corrections (such as probation and parole) so that offenders for whom prison is not necessary are adequately supervised.

Who else is working on it?

Several foundations and the United States federal government are working on various aspects of criminal justice reform. Our perception is that organizations can roughly be divided into those that frame reform in terms of the rights of defendants and people in prison and organizations making a case that focuses on improving public safety and reducing public spending on incarceration by saving jail and prison beds for high risk offenders (and thus seeks to appeal to conservatives as well as progressives).

How much of an impact could we have?

We are very uncertain about how big of a humanitarian impact we could expect for a given level of funding for criminal justice reform. Based on claims in states that have already adopted reform packages, we would guess that reducing prison populations by about 10% while having a neutral or slightly positive impact on public safety could be a reasonable near-term goalpost. In the longer term, we’d guess that much larger reductions might be possible if community corrections are strengthened and the political dialogue around criminal justice policy continues to improve.

1. Why we are interested in criminal justice reform

We initially became interested in criminal justice reform because policy generalists we spoke with during our broad exploration of U.S. politics and policy advocacy indicated to us that it was an unusually promising — and in particular, unusually tractable — cause.4 Specifically, we heard from multiple sources that the combination of the adverse U.S. fiscal situation, declining crime rates, and emerging conservative interest in an issue historically supported by progressives may have created a “unique moment” for criminal justice reform with a limited window.5

Upon investigation, we learned that more than two dozen states, supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Public Safety Performance Project (PSPP) and the federal government’s Bureau of Justice Assistance, have passed criminal justice reform legislative packages since 2007.6 We are unaware of any equally important U.S. public policy cause that can match this extensive wave of reforms nor of any other policy organization deeply involved in so much recent legislation, which reinforced our view that criminal justice reform stands out for its political momentum. The strong possibility of observing substantial policy change in the short-term, combined with the possibility to work in multiple states, suggested that criminal justice reform might be a particularly good opportunity to learn about policy advocacy.

Criminal justice reform also stands out because we quickly identified (a) a set of innovative ideas that seemed potentially high impact and underfunded and (b) a set of researchers, specialists, and technical assistance providers ready to promote these ideas with additional funding. In particular, we learned about certain proposals such as making responses to offenses more “swift and certain,” improving community corrections (for example, by using electronic monitoring or improved risk assessment), designing regulations for cannabis in Washington and Colorado (where recreational use is now legal according to state law), and reducing the prevalence of binge drinking and alcohol use disorders, that aim to reduce incarceration with a neutral or positive effect on public safety. Mark Kleiman (more) and Angela Hawken (more) are academics who work on these types of policies and we believe each could expand their work with more funding.

2. The problem

The United States is burdened both by a very high incarceration rate and by a high (but declining) crime rate. In 2012, there were about 1.5 million Americans in prison and 750 thousand in jails, for a total of about 2.2 million incarcerated Americans.7 The United States incarcerates more residents as a proportion of its population than almost any other country in the world.8 The incarceration rate is not necessarily driven entirely by criminal justice policy, however; the United States may also have more crime than other developed countries. The U.S. homicide rate is more than twice as high as the OECD average of 2.23 homicides per 100,000 people.9

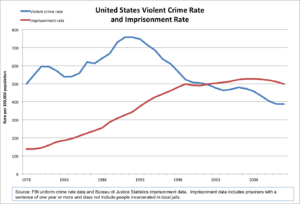

(A larger version of this graph is available here).

As shown by the above figure, since the 1990s, violent crime in the United States has fallen dramatically while incarceration rates have continued to increase.10 Rising incarceration rates in the context of falling crime could be taken to suggest that the U.S. incarcerates too many residents, but it is also possible that increased incarceration contributed to declining crime by incapacitating those most likely to commit crimes. Criminologists have attempted to disentangle these factors, but confounding factors impede rigorous analysis and we have not seen good studies nailing down the high incarceration rate’s effect on crime.11 Still, it has been argued (and seems probably correct) to us that, while initial increases in incarceration may have reduced crime, at the current margin, higher incarceration does not have large benefits for public safety.12 In particular, we’d guess that sentences in the United States are too long and too inconsistently applied and that strong community supervision (combined with the threat of short stints in jail) is not adequately used as an alternative to incarceration for low-risk offenders.

We have not attempted to carefully quantify the costs of the high incarceration rate but we believe those costs to be quite high along many dimensions:

- The fiscal costs to states and the federal government13

- The suffering of people who are incarcerated.

- The economic costs of lost earnings by those prisoners who would have been employed had they not been incarcerated.14

- Economic costs due to decreased earnings by ex-offenders after they are released from prison.15

- The costs to the families and communities of those who are incarcerated. As of 2010, 2.7 million minor children had a parent behind bars, potentially leading to a host of problems.16 Additionally, as of 2007, one in nine young black men was behind bars.17 We’d guess that high incarceration rates might have particularly negative effects in communities where incarceration has become a normative experience, potentially impacting family formation. The costs of crime may also be concentrated in black communities.18

3. Possible interventions

Many criminal justice reforms fall into one of two categories. Front-end reforms affect individuals at their first point of contact with the criminal justice system. Back-end reforms affect individuals after they have already entered the criminal justice system. Some examples of front-end reforms include reducing or improving the use of pretrial detention, increasing the use of alternatives to incarceration, decriminalizing some activities (such as the possession or sale of drugs), improving the quality of legal representation for criminal defendants, changing policing policies, and shortening sentences. Some examples of back-end reforms include increasing eligibility for parole, minimizing the frequency or severity of probation and parole revocations (for example by increasing the swiftness and certainty of responses), and improving community corrections to try to minimize recidivism.

Additionally, improving prison conditions may reduce the suffering of those in prison and some policy reforms outside of the criminal justice system (such as reducing lead exposure or fetal alcohol exposure) may be able to reduce crime.

We have not deeply vetted the entire range of policy changes proposed by criminal justice advocates and do not have a firm position on which reforms are most beneficial. That said, because we believe that crime and incarceration both have high costs, we are most enthusiastic about reforms that seem to reduce incarceration while improving (or at least maintaining) public safety.

3.1 Ideas promoted by Mark Kleiman

Mark Kleiman is a researcher who studies and promotes approaches to crime control with the potential to simultaneously reduce crime and incarceration.19 Dr. Kleiman also worked as a consultant to advise the state of Washington on implementing the legalization of recreational cannabis.20 We think that a set of reforms propounded by Dr. Kleiman, some of which have been studied by Angela Hawken, seem particularly promising. These reforms include:

- Swift and certain sanctions exemplified by Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) program. Mark Kleiman, Angela Hawken, and other criminal justice specialists believe that misbehavior can be deterred more strongly with less punishment if punishment is distributed more consistently and closer to the time the offender misbehaves.21 The current criminal justice system (particularly the probation and parole systems) attempts to use harsh punishments to make up for the inconsistency of enforcement. Advocates of swift and certain responses believe this approach is ill-suited to human psychology and particularly to the psychology of those most likely to commit crimes, who are likely to have trouble with long-term planning. The last fifteen years of a twenty year sentence, these advocates believe, have very high cost but very low additional deterrent effect.22 Swift and certain sanctions aim to improve the efficiency of the criminal justice system and to decrease crime with less punishment.In HOPE, Hawaii Judge Steven Alm implemented a version of swift and certain sanctions by frequently, yet randomly, drug testing probationers and, instead of revoking those who failed from probation altogether, sentencing them immediately to a jail stay of a few days.23 Initial evidence from a randomized controlled trial of HOPE, which we have not vetted, was very positive, though some have expressed uncertainty about whether the program is replicable and whether its effects will be sustained over the long-run.24 Studies of other programs implementing swift and certain sanctions may have also shown promising results.25Dr. Kleiman believes that, despite the initial success of HOPE and other programs, there is a lack of funding for research on and implementation of swift and certain sanctions.26

- GPS position monitoring. GPS position monitoring has the potential to reduce both crime and incarceration by enabling law enforcement to closely supervise offenders without putting them behind bars.27 For under five dollars a day, offenders could be given tamper-evident ankle monitors so that it would be immediately evident to their supervisors if they were at the location of a crime.28 This technology might enable some prisoners to be more quickly released back into the community (or to avoid incarceration altogether) without risking public safety. The large number of crimes currently committed by those on probation or parole might also be reduced by this technology.29 Lastly, in addition to its potential to improve the quality of supervision, position-monitoring also opens up the possibility of graduated punishments, such as curfews, that are less severe and have fewer collateral consequences than incarceration but that might still deter or incapacitate many offenders.30 However, Mark Kleiman stated to us that GPS position monitoring has not yet been subject to much testing and has a very bad reputation among practitioners because of its use for actively monitoring sex offenders.31

- Drug policy reforms with potential to reduce abuse and incarceration.

- Regulating cannabis in Washington State and Colorado. Dr. Kleiman believes that the cannabis markets in Washington State and Colorado will end up promoting themselves to heavy users like the alcohol market does unless advocacy and technical assistance to state governments lead to responsible regulation.32 Dr. Kleiman was part of a group that worked with Washington State on its implementation of cannabis legalization and has suggested multiple ways to try to limit the costs of legalization and decrease marketing to abusers.33

- Reducing the prevalence of binge drinking and alcohol use disorders. Dr. Kleiman told us that alcohol abuse is the most important public policy issue that [he] can think of that has no major advocate at the moment.34 According to Dr. Kleiman, reducing binge drinking by, for example, raising the alcohol tax or prohibiting drinking among past abusers would lower crime and have an immediate effect on the homicide rate.35 However, increasing regulation of alcohol could be politically difficult.36

3.2 Ideas promoted by the Pew Public Safety Performance Project

The Pew Public Safety Performance Project (PSPP) supports various evidence-based corrections and sentencing reforms intended to help states maximize the return on their public safety spending. These reforms include:

- Risk and needs assessments of offenders to improve decisions about detention, incarceration, release, supervision, and treatment

- Accountability measures to ensure the use of evidence based practices, and/or develop data reporting requirements

- Good time and earned time credits that reduce the sentences or length of community supervision for inmates who behave well in prison or participate in programs designed to reduce recidivism

- Intermediate and graduated sanctions, often based on HOPE, to deter bad behavior

- Increased funding for community based treatment such as substance abuse programs and reentry plans

- Sentencing changes

- Mandatory supervision requirements to ensure that high risk offenders are supervised after being released from prison

- Problem solving courts, which are often focused on offenders with substance abuse or mental health disorders

- Streamlined and expanded parole to reduce incarceration while protecting public safety by expanding post-release supervision.37

While these are among the most common reforms, the specific reforms in each state are tailored to each state’s needs. PSPP’s population impact projections in the participating states estimate that these types of reforms can reduce state prison populations by 5% to 25%.38 We hope to discuss these reforms in more detail in an upcoming writeup.

3.3 Strategy recommended by Steve Teles

Steve Teles is a political scientist at Johns Hopkins who has written about philanthropy’s role in political movements and in policy advocacy. Prof. Teles is the only person we’ve come across who has extensively studied the historical role of philanthropy in politics, and seems to have a broad view of the different ways in which philanthropy can influence policy. We have hired Dr. Teles part-time as a consultant and his work for us on criminal justice reform has informed many parts of our investigation.

Dr. Teles believes that with vastly intensified community corrections and alternatives to incarceration in place, incarceration rates could be safely reduced by up to 50%. To do this, we would need to substantially expand the advocacy infrastructure around criminal justice reform and might need to move beyond the specific interventions listed above.39

Various political and advocacy strategies, including policy research, legislative advocacy, technical assistance to policymakers or practitioners, litigation, communications and public education, funding direct services, and funding pilot projects could be used to pursue these policies. We are still learning about what might be the most fruitful strategies for achieving promising reforms. Two tactics that have struck us as particularly promising are providing technical assistance to state policymakers through the justice reinvestment process and engaging conservatives advocating reform. PSPP uses both these tactics, and we plan to elaborate in a future writeup.

We also believe that building an infrastructure to advocate for swift and certain responses to offenses and to provide technical assistance to policymakers and practitioners interested in those principles might be particularly effective. Our grants to Mark Kleiman (more) and Angela Hawken (more) are, in part, intended to provide tools to practitioners implementing or evaluating swift and certain sanctions.

4. Who else is working on it?

Several national foundations are involved in criminal justice reform.

| FUNDER | BUDGET | FOCUS AREAS |

|---|---|---|

| The Open Society Foundation (OSF) | Budget of slightly under $15 million per year on criminal justice reform and an additional $7.8 million per year on their Campaign for a New Drug Policy.40 | OSF appears (based on our scanning their list of grants) to focus on the death penalty and drug decriminalization. |

| The Pew Public Safety Performance Project (PSPP). | PSPP does not make its annual budget publicly available. We hope to discuss PSPP more in a future writeup. | PSPP is a program of the Pew Charitable Trusts a public charity. PSPP focuses on providing technical assistance to states seeking to improve their return on public safety spending, engaging with nontraditional allies of criminal justice reform (such as conservatives, law enforcement groups, and victims’ advocates), and research and public education.41 |

| The Laura and John Arnold Foundation (LJAF) | LJAF made $5.5 million in criminal justice grants over three years from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2013.42 LJAF may also perform some criminal justice related work directly using its operating budget. | LJAF focuses on “the front end of the system, which runs from arrest through sentencing, and forensic science.”43 |

| The Ford Foundation | Ford appears to have spent about $2.8 million on criminal justice grants in 2013.44 | The Ford Foundation appears (based on scanning their list of grants) to be focused on supporting public defense, building a criminal justice reform advocacy infrastructure, and Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion in Seattle.45 |

| Atlantic Philanthropies | Atlantic Philanthropies spent about $9.8 million on criminal justice related grants in 2012 (the most recent year for which we have data). We expect this number to go down over time because the foundation is winding down.46 | Atlantic Philanthropies appears (based on scanning their list of grants) to focus heavily on capital punishment related work.47 |

| Public Welfare Foundation | Public Welfare’s Criminal Justice Program budget is about $6 million per year.48 | The Public Welfare Foundation focuses on pretrial detention reform, sentencing reform, and racial disparities.49 |

| The Smith Richardson Foundation (SRF) | SRF spends about $1.5 million per year on criminal justice policy.50 | SRF exclusively funds research.51 |

We believe that we have identified all of the large U.S. foundations with major criminal justice programs, but do not believe that this is an exhaustive list of all funding in the area. For example, many local foundations may work on criminal justice reform. We have identified somewhat less than $60 million per year in criminal justice reform funding by foundations (not including some spending that is strictly on drug policy). The federal government and state governments also promote criminal justice reform including through the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, a partnership with PSPP. We do not know how much the public sector spends on this cause. On the other hand, we used a very broad definition of criminal justice reform funding, so our estimate of total funding includes many projects that are not primarily intended to promote comprehensive reform. For example, the Ford Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies support some direct legal services, such as public defense and capital defense, and the Open Society Foundation focuses much of its resources on opposing capital punishment.

We have heard from various public policy and criminal justice reform experts that the field as a whole could use additional funding, but we don’t yet have very strong beliefs about the size of an adequately funded advocacy field, so we are relatively agnostic about this question.

We have, however, identified some areas where there appear to be gaps in existing funding. For example, there is no organization dedicated to promoting and providing technical assistance to jurisdictions interested in implementing swift and certain responses to offenses.52 More generally, we believe that there is room to fund certain evidence-based criminal justice reforms that focus prison beds on the highest risk offenders, try to build on support from moderates and conservatives, and prioritizing public safety while improving the efficiency of corrections spending.

While many of the above funders may fund some organizations that share this perspective, only three major foundations – Pew, LJAF, and SRF – seem very concentrated in this area of focus. In addition, we’ve spoken with two nonprofits whose approach seems, at least in part, aligned with ours. The Vera Institute of Justice’s Center on Sentencing and Corrections (CSC) provides technical assistance to governments seeking to improve their public safety spending and has worked with PSPP to provide assistance to states implementing data-driven reform through the Justice Reinvestment Initiative.53 CSC’s staff includes about twenty employees.54 The Brennan Center for Justice is a “part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub,” whose Justice Program is focused on using “data-driven research” to reduce mass incarceration and reform the criminal justice system’s frontend.55 The Justice Program has about eight staff members.56 We do not know the budget of either of these organizations nor do we know the extent to which their funding comes from the foundations mentioned above.

Overall, we would guess that there is less than $20 million per year being spent by organizations (other than governments) on the types of reforms we are most interested in as detailed above.

We have also heard that there is a lack of funding for policy reforms, for reforms to the nexus between immigration and the criminal justice system, for front-end reforms, for national-level reform, for interdisciplinary research, and for efforts to improve prison conditions, but we have not investigated these claims in detail.57

5. How much of an impact could we have?

We are very uncertain about how much additional policy change various levels of funding might lead to in this space, the magnitude of prison population reduction that would be achieved by various policy changes, and the effects various policy changes might have on other variables such as the crime rate or the economy. We are also very uncertain about how much we should value reductions in prison time served relative to other potential outcomes (for example, additional income or years of life, or the ability to migrate from a developing country to a rich country).

We have, however, done back of the envelope calculations to get a sense of whether plausible near-term reforms would be important enough to justify our investment in this area. We do not yet know how ambitious our longer-term goals might be were we to invest in this area over multiple years.

- Justice reinvestment. Justice reinvestment is a partnership through which PSPP and the federal government’s Bureau of Justice Assistance provide technical assistance to states so that they can improve the efficiency and reduce the costs of the criminal justice system and then use those cost savings to fund evidence based public safety practices, improving the overall state budget.58 Much of the criminal justice legislation passed since 2007 came out of the justice reinvestment process. Specifically, through 2013, twenty-nine legislative reform packages had been passed in twenty-seven states through justice reinvestment.59On average, PSPP forecasts that in the states in which it has worked, prison populations will fall about 11% in the five years after reform relative to what would have happened in reform’s absence. We hope to give our assessment of these forecasts in a future writeup focused on PSPP. Justice reinvestment’s track record suggests to us that a 10% further reduction in incarceration is ambitious but not infeasible.For an in depth overview of justice reinvestment, please see the Urban Institute’s assessment here. Our own full review of PSPP, including its justice reinvestment work, is near completion and should be published shortly.

- Scaling swift and certain responses (exemplified by HOPE). As discussed above, HOPE is a program in which particularly high-risk probationers are transferred from normal probation into a swift-and-certain sanctions regime, in which they are subjected to randomly scheduled drug tests and immediately given brief jail stays for each probation violation60The randomized controlled trial of HOPE, which was restricted to drug-involved probationers who were not on supervision for domestic-violence or sex offenses, estimated that the average time spent in prison per probationer was reduced from about 134 days behind bars to about 69 days, an average difference of 65 days.61 In addition, no-shows for probation appointments, positive urine tests, new arrest rates, and probation revocation rates all decreased by half or more, suggesting that HOPE may also have positive effects on public safety.62About two million persons entered probation in the United States in 2012.63 It is difficult to guess at the coverage that could be reached through an ambitious but pragmatic expansion of swift and certain responses, especially because we do not know whether the intervention would have strong effects on probationers other than the specific population covered by the HOPE RCT (high risk, drug-involved probationers neither under supervision for sex crimes nor for domestic violence). However, we’d guess that a successful campaign for the adoption of swift-and-certain might scale to one fourth of probationers.64If HOPE achieved the same results after being scaled to one fourth of the people entering probation in a given year, it would reduce the number of people incarcerated at a point in time by about 90 thousand people.65There were about 2.2 million incarcerated people in 2012, so this would be a decrease of about 4%.66 It strikes us as possible that a major advocacy push combined with major investments in criminal justice infrastructure and administration might lead to a more extensive roll out of swift-and-certain or to an expansion of HOPE’s principles to contexts beyond probation.67 It’s also possible that additional research on HOPE would lead to improvements and better-calibrated responses to offenses. However, this possibility is quite speculative and it’s quite possible that the results of HOPE would not be replicated at scale.68

- Effects of a 10% reduction in incarceration rates. Based on the above points, we would guess that a 10% reduction in incarceration rates, with a neutral or positive effect on public safety, is a reasonable back of the envelope baseline for a very successful criminal justice reform campaign. Below, we discuss our very rough sense of the social impact of such a win.

- Years of incarceration averted. In 2012, there were about 2.2 million people incarcerated.69 Reducing the incarcerated population by 10% for 10 years would therefore avert 2.2 million person years of incarceration.70

- Fiscal savings Total state corrections expenditures were about $48.5 billion in 2010.71 We’d guess that a 10% reduction in incarceration would lead to somewhat less than a 10% reduction in corrections spending because some of the reduction in incarceration will be achieved by strengthening community corrections and because the marginal cost of incarceration may be less than the average cost. We’d therefore very roughly guess that a 10% reduction in incarceration would lead to a 5% reduction in corrections spending and savings of $2.4 billion per year.72 Thus, over the course of ten years, we’d guess that successful, ambitious reform would save states about $24 billion on the costs of incarceration. However, the total impact on state budgets would probably be somewhat smaller because investments in improving community corrections would be required to facilitate these reductions in incarceration. It is possible that further reductions in incarceration could be safely achieved if large portions of these savings were spent on programs attempting to lower recidivism or alternatives to incarceration, but we have not carefully investigated the effectiveness of such programs.

- Diffuse effects and effects on other outcomes. We’d hope that funding groups that study and spread data-based criminal justice policies designed around effectiveness instead of designed to make politicians appear “tough on crime” would have additional diffuse effects on improving the U.S. criminal justice debate. However, we find it difficult to estimate the magnitude of these effects and do not factor them into this discussion. This analysis also does not focus on possible reductions in crime. We’ve seen some evidence that these effects might be substantial, but we have not tried to quantify these effects.

- The potential for much larger reductions. Prof. Steve Teles believes that for a sufficiently ambitious effort, including substantial expansion of advocacy infrastructure on many dimensions, impacts in the range of a 50% reduction in incarceration could be achievable.73

6. What have we done so far?

Criminal justice reform stands out to us in part because we found impressive people and organizations with innovative ideas who were struggling to get adequate funding. These opportunities suggested to us both the possibility of making an impact and also the possibility of learning quickly from our grantees.

We discuss below the grants that we have made so far.

6.1 Grant to support Mark A.R. Kleiman, Professor of Public Policy at UCLA

We first decided to speak to Dr. Kleiman because of his work researching and promoting the concept of swift and certain sanctions, which Matt Stoller and Aaron Swartz found to be a potentially promising policy and because his work was recommended to us by Steven Teles.74

During our conversations with him, Dr. Kleiman presented us with policy ideas aimed at reducing crime and incarceration that struck us as innovative, potentially high-impact, and neglected. These ideas included:

- Swift and certain sanctions (more above)

- Position-monitoring (more above)

- Reducing alcohol abuse by, for example, increasing alcohol taxes (more above)

- Regulating cannabis in Washington State and Colorado. Some ideas Dr. Kleiman thought would be worth trying out or studying to prevent recreational cannabis legalization from harming heavy users included:

- Allowing home delivery of cannabis.

- Allowing individuals to set their own quotas (alterable only with thirty days notice) as a commitment mechanism to avoid using more than they intend.

- Setting limits on the amount of THC that could be produced.

- Studying the retail process and ways for the state to dissuade abuse such as labels or other forms of communication.

- Setting levels of cannabis taxation such that the price of legal cannabis will neither be much higher than its current, illicit price (which would incentivize a continued illicit market) nor much lower (which would increase abuse)75

- Refocusing international narcotics enforcement on violence prevention76

- Researching the possible beneficial effects of some illicit drugs77

These ideas struck us as potentially innovative, insightful, and pragmatic. Dr. Kleiman believes that, without regulation, legalized cannabis markets may be dangerous to heavy users (see above) or lead to a backlash.78

As our investigation of criminal justice reform moved forward, we heard that Dr. Kleiman is excellent at navigating the intersection of research and policy and we learned that there does indeed seem to be a lack of research funding and attention toward his ideas relative to our impression of their promise (see above for a discussion of existing funding for criminal justice reform).79

We asked Dr. Kleiman about his need for more funding and his team’s priorities. Dr. Kleiman told us that he could use $250,000 to $300,000 on immediate, time-sensitive research and technical assistance and could usefully spend up to $1 million per year if additional funding priorities were included.80 He also told us that his application to a foundation for $175,000 to work on these issues had recently been rejected.81

Dr. Kleiman also sent us a prioritized list of fifteen specific projects and their budget estimates. The top six projects, totaling $245,000, were:

- Alcohol cross-elasticity Dr. Kleiman believes alcohol abuse is a serious threat to public safety and cannabis use could be a complement or substitute for alcohol use, so cannabis policy’s effects on alcohol use could be an important component of its costs or benefits. He proposed to “use the natural experiment created by difference in cannabis policy between Western and Eastern Washington to measure the impacts of cannabis availability on alcohol sales and on health and public-safety outcomes.”82

- Outcome list and data-gathering plan. In order to learn from the experiments with legalization in Washington and Colorado, it could be important to have baseline data from before legalization has had its effect. Dr. Kleiman proposed to identify the most relevant outcomes for evaluating legalization, determine how to measure those that are measureable, determine which must be measured before legalization is implemented, and then estimate the cost of carrying out time-sensitive data-gathering.83

- Online implementation tool for swift-and-certain sanctions programs. Dr. Kleiman proposed to create a website to provide information to jurisdictions interested in implementing swift and certain sanctions for probation and parole violations.84

- Swift-and-certain mechanism study: self-command and procedural justice. In order to learn more about the mechanisms behind the success of swift and certain sanctions and to improve program design, Dr. Kleiman proposed to “develop and field-test instruments to measure self-command, delayed gratification, and perceptions of fairness among offenders subject to swift-and-certain sanctions programs to determine which, if any, predict outcomes.”85

- Optimal cannabis taxation. Dr. Kleiman proposed to “[d]etermine the optimal level and basis of cannabis taxation for states now legalizing, balancing considerations of health, public safety, revenue, and administrative feasibility.”86

- User-determined quotas. Dr. Kleiman proposed to study the possibility of implementing user-determined quotas to help cannabis users avoid problem use.87

We were surprised to learn that, in a field with so much attention, Dr. Kleiman had not already found funding for his agenda, and was planning to allocate the same staff time to for-profit consulting if he could not find funding for this work. Good Ventures made a $245,000 grant to the Washington Office on Latin America, which will be used to support Dr. Kleiman’s research. While the grant amount was designed to be enough to fund the above six projects, it is unrestricted and Dr. Kleiman is free to use the funding for other research opportunities if they arise.

Dr. Kleiman’s descriptions of his proposed projects are available here.

Another donor has since donated an additional $70,000 to support the projects on Dr. Kleiman’s list, also unrestricted and also at our recommendation.

We published an update on this grant in May, 2015.

6.2 Grant to support Angela Hawken, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Pepperdine University

Dr. Angela Hawken is an associate professor of public policy at Pepperdine University, where her research focuses on “drugs, crimes and corruption.”88 We were referred to Dr. Hawken by Steven Teles, who knew about her work leading the randomized controlled trial of HOPE, and by Dr. Kleiman, who has frequently collaborated with her.89

Dr. Hawken’s current project, BetaGov, aims to generate knowledge about what works in the public sector (in areas including but not limited to criminal justice) by serving as a repository for practitioners’ ideas to be tested, serving as a database of results to facilitate learning across studies, and providing a toolkit (including web-based training, webinars, assessment tools, and an RCT call-in hotline) so that practitioners can conduct their own RCTs.90 Dr. Hawken believes that Ph.D.’s are not necessarily needed to implement randomized controlled trials in all cases, and that by collecting ideas, enabling and encouraging practitioners to conduct RCTs, and sharing the results, BetaGov will dramatically increase the evidence available for public sector programs 91

At the time we began funding BetaGov, Dr. Hawken was already working with two jurisdictions seeking to test out variations on swift-and certain sanctions (Washington State and a jurisdiction in a western state), suggesting that there is demand for BetaGov’s service.92

Dr. Hawken’s rough estimate is that BetaGov’s full budget would be “on the order of $2 million for a five-year period.”93 We hope to make BetaGov’s budget and proposal public shortly.

We are interested in promoting an attitude toward the criminal justice system (and public policy in general) that values evidence and outcomes. Facilitating randomized controlled trials by practitioners seems like a good way to encourage this approach among policymakers and implementers on the ground. We believe that BetaGov’s efforts to increase the evidence base in the field of criminal justice may be an important complement to our other efforts to take advantage of the bipartisan interest in policy change in this field.94 We have therefore made a $200,000 grant to Pepperdine University to provide BetaGov with seed funding. We plan to follow up with BetaGov and would consider providing additional funding if the project is successful.

6.3 Pew Public Safety Performance Project (PSPP)

PSPP provides technical assistance to states seeking to reform their criminal justice laws through the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, a partnership between PSPP and the federal government’s Bureau of Justice Assistance. Over two dozen states have passed legislative packages with PSPP’s assistance, a track record that we believe stands out in the field of politics and reveals an impressive ability to work with policymakers. These packages typically included reforms aimed at improving states’ returns on their public safety spending and focusing prison beds on the highest risk such as improving sentencing, improving pretrial systems, streamlining and expanding parole, implementing swift and certain responses to violations by probationers and parolees, increasing and improving community corrections, and establishing oversight and performance packages (see above for more discussion of reforms promoted by PSPP).

PSPP also engages in broader efforts to change the tenor of the debate on criminal justice reform from one that focuses on the divide between “tough” v. “weak” on crime to one that focuses on being “smart on crime” and implementing evidence-based policies. To do so, PSPP has engaged with and supported nontraditional allies of criminal justice reform such as conservatives (including Right on Crime and the Justice Fellowship), victims’ advocates, and law enforcement.

PSPP’s focus on incarceration’s fiscal costs and on improving the return states get on their public safety spending seems to have successfully engaged policymakers and stakeholders across ideologies and is consistent with our belief that the potential for bipartisan collaboration makes criminal justice reform a particularly tractable cause. While we find it difficult to rigorously evaluate policy advocacy and technical assistance, we are impressed with PSPP’s track record and believe that they played a major role in achieving or improving the quality of a substantial number of beneficial reforms.

We are considering a $3 million grant to PSPP over a two-year period. A full review of PSPP is near completion.

7. Open questions

- What is the relationship between incarceration and public safety? How does this differ among various reforms? What incarceration rate and crime rate should we expect if the criminal justice system is functioning well?

- What are the expected impacts on crime and incarceration of the most plausible reforms that are currently on the table? What effect should we expect from broader advocacy strategies?

- What is the appropriate level of funding for different criminal justice reform strategies? How much of an effect on policy should we expect from differing levels of funding? How does this differ by the type of strategy? Is it possible that the field has developed far enough that reform will happen even without additional funding?

- How do moderate reforms affect the possibility of achieving large-scale reforms? Do moderate reforms make larger-scale reforms more likely by moving policy and dialogue in the right direction or do they subvert large-scale reforms by drawing away attention and resources?

- What could be accomplished by developing a strategy that attempted to more aggressively increase the attention paid to criminal justice issues, expand political possibilities, and design additional interventions?

8. Our process

Good Ventures began exploring drug policy reform, a field closely connected to criminal justice reform, in 2012 with a grant to the Drug Policy Alliance followed by a report on the topic researched and written by Matt Stoller and Aaron Swartz. We initially learned about Mark Kleiman through this report.

In the spring of 2013, we began to investigate the broad cause of policy-oriented philanthropy and spoke to U.S. public policy generalists including Steven Teles, Gara LaMarche, and Mark Schmitt, and gained the impression that criminal justice reform is a promising cause with a “window of opportunity” for policy change.95 Dr. Teles, in particular, argued that this cause represented the best available opportunity to find good U.S. giving opportunities quickly and make relatively short-term progress.96

Over the summer and fall of 2013, we had broad conversations about criminal justice reform with experts in the field and with criminal justice reform specialists and many of the field’s biggest funders. Public notes are available from our conversations with:

- Mark Kleiman, Professor of Public Policy, UCLA School of Public Affairs

- Adam Gelb, Director, Pew Public Safety Performance Project

- Seema Gajwani, Program Officer for Criminal Justice, Public Welfare Foundation

- Ken Zimmerman, Director of U.S. Programs, and Leonard Noisette, Director of the Justice Fund for U.S. Programs, Open Society Foundation

- Mark Steinmeyer, Senior Program Officer, Smith Richardson Foundation

- Inimai M. Chettiar, Director of the Justice Program, Brennan Center for Justice

More recently, our conversations have focused on evaluating specific funding opportunities. Public notes are available from such a conversation with Mark Kleiman and Angela Hawken. We expect additional public notes to be forthcoming.

Our research has particularly but not exclusively investigated approaches to criminal justice reform focused on improving public safety and reducing state spending on incarceration by saving prison beds for high-risk offenders because we learned early on that this approach seems underfunded relative to its promise. Dr. Teles, whom we have hired as a part-time consultant, has also played a major role in helping us to design our criminal justice reform strategy and in sourcing opportunities. We continue to be open to learning about more opportunities in this space and may make additional grants in the future.

9. Sources

| DOCUMENT | SOURCE |

|---|---|

| Angela Hawken email to GiveWell on September 17, 2013 | Unpublished |

| Angela Hawken homepage | Source |

| BetaGov proposal | Unpublished |

| Brennan Center website | Source |

| Bureau of Justice Statistics. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2012 | Source |

| Bureau of Justice Statistics. Criminal Victimization, 2012 | Source |

| Bureau of Justice Statistics. State Corrections Expenditures, FY 1982-2010 | Source |

| GiveWell spreadsheet compiling criminal justice grants | Unpublished |

| GiveWell’s notes from a July 26, 2013 conversation with the Open Society Foundation | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes from a September 10, 2013 conversation with Mark Steinmeyer | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes from an August 27, 2013 converstion with Matt Stoller | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on a July 2, 2013 conversation with Mark Kleiman | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on a June 12, 2013 conversation with Steve Teles | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on a November 12, 2013 conversation with Mark Kleiman | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on a September 16, 2013 with Angela Hawken | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on an August 22, 2013 conversation with Inimai M. Chettiar | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on an August 23, 2013 conversation with Adam Gelb | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on an August 28, 2013 conversation with Seema Gajwani | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on an October 31, 2013 conversation with Gara LaMarche | Source |

| GiveWell’s notes on May 22 and June 14, 2013 conversations with Mark Schmitt | Source |

| Hawken and Kleiman 2009 | Source |

| LaVigne et al 2014 | Source |

| LJAF website. Areas of Focus | Source |

| LJAF website. Grants | Source |

| Mark Kleiman email to GiveWell on April 28, 2014 | Unpublished |

| Mark Kleiman homepage | Source |

| Mark Kleiman. Proposed project list. | Source |

| Mark Kleiman. Smart on Crime | Source |

| Mark Kleiman. The Outpatient Prison | Source |

| National Institute of Justice. Swift and Certain Sanctions | Source |

| OECD. How’s Life? 2013: Measuring Well-Being | Source |

| Pew Presentation to Good Ventures and GiveWell | Unpublished |

| Pew Public Safety Performance Project. Sentencing and Corrections Reforms in Justice Reinvestment States | Source |

| Pew. Collateral costs: incarceration’s effects on economic mobility | Source |

| Pew. One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008 | Source |

| Schmitt, Warner, and Gupta 2010 | Source |

| Steve Teles conversation with GiveWell on May 9, 2013 | Unpublished |

| Steve Teles email to GiveWell on April 24, 2014 | Unpublished |

| Steve Teles email to GiveWell on March 1, 2014 | Unpublished |

| Vera Center on Sentencing and Corrections Website | Source |